A couple incurs a marriage penalty if a couple pays more income tax filing as a married couple than the two of them would pay if they were single and filed as individuals. Conversely, a couple receives a marriage bonus if they pay less tax filing as a couple than the two of them would pay if they were single.

Marriage penalties and bonuses occur because income taxes for married couples generally are based on the combined income of a couple, not on the incomes of each spouse individually. Under a progressive income tax, a couple’s income can be taxed more or less than that of two single individuals. A couple is not obliged to file a joint tax return, but their alternative—filing separate returns as a married couple—almost always results in a higher tax liability.

Marriage penalties are more common when spouses have similar incomes, and bonuses are more probable when spouses have disparate incomes. Married couples with children are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples without children because one or both spouses could use the head of household filing status if they were able to file as unmarried. Under certain circumstances, tax provisions that phase in or out with income may produce marriage bonuses or penalties.

The Tax Policy Centers estimates that in 2018. the individual income tax system caused 43 percent of married couples to face marriage penalties and another 43 percent to receive bonuses. The remainder did not experience either a tax-related penalty or bonus (largely because they did not owe any income taxes). Among those with marriage penalties, the average penalty was $2,064. The average marriage bonus was $3,062 for those couples receiving a bonus.

Those estimates do not reflect the experiences of unmarried individuals who may also incur tax penalties or bonuses by their decisions to not marry. Because married and unmarried individuals may not be similar in many respects, the impact of marriage on the two groups’ tax liabilities could be very different. However, estimating the effect of marriage on the tax liabilities of unmarried individuals requires making assumptions about whom an unmarried individual would marry; even among cohabitating partners, data limitations often prevent analysis of the tax benefits and costs of marriage.

Married penalty calculations are different for couples with and without children. If tax brackets for joint filers are less than half the width as for single filers, a childless couple is more likely to incur a marriage penalty if both work and earn similar amounts than a one-earner couple. In that situation, combining incomes in joint filing can push the two-earner couple into a higher tax bracket than both would face if filing single returns.

In 2023, that situation happens only for couples with income above $693,750 but it was more common before the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act widened the brackets for joint filers whose income was below that threshold.

Even with joint-filer brackets twice as wide as single-filer brackets, a couple with children can still face a marriage penalty because single parents have the option to file as heads of households. Consider parents of two children, each parent earning $100,000 (table 1). Filing jointly and taking a $27,700 standard deduction, their taxable income is $172,300, for which their 2023 income tax liability is $24,521. If they could file separately, one spouse as single and the other as the head of a household, the single filer would owe a tax of $14,261 and the head-of-household filer would owe $7,125, yielding a total tax of $21,386. Their joint tax bill is thus $3,136 higher than the sum of their hypothetical individual tax bills, imposing on them a marriage penalty equal to 1.6 percent of their adjusted gross income.

Couples are more prone to receive a marriage bonus when one spouse earns all or most of their income. In those cases, joint filing shifts the higher earner’s income into a lower tax bracket.

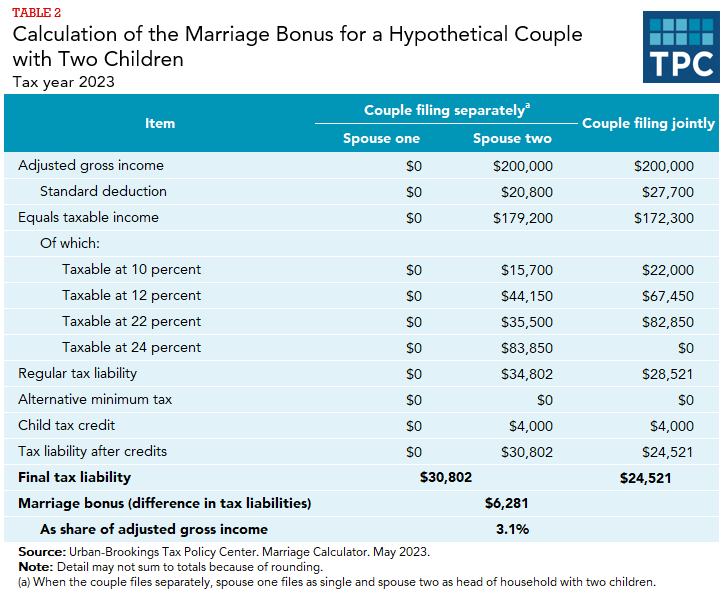

Consider a couple with two children and $200,000 in total earnings, all earned by spouse two (table 2). Under 2023 tax law, filing a joint return rather than having spouse two file as head of household, would yield the couple a marriage bonus of nearly $6,281, or 3.1 percent of their adjusted gross income. One reason for this result is that tax brackets for joint returns (other than the 35 percent bracket) are wider than those for head-of-household returns. As a result, much of the couple’s income is taxed at lower rates under joint filing than if spouse two filed as a head of household. Second, the couple would benefit from a larger standard deduction. Couples filing jointly receive a $27,700 deduction in 2023, while heads of household receive $20,800.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) temporarily limited many of the marriage penalties higher-income earners face, though penalties still exist. Except for the 35 percent bracket, all tax brackets for married couples filing a joint return are currently exactly double the single brackets. This limits a main cause of previous marriage penalties. It also expands the potential for marriage bonuses, as more couples find that filing together moves some income into lower tax brackets.

Additionally, the child tax credit phaseout now begins at $400,000 for couples, again double the $200,000 starting point of the phaseout for singles. Prior law began phasing out the credit at $75,000 for singles and $110,000 for couples, which could have introduced another marriage penalty for couples with children.

The phaseout of the alternative minimum tax exemption is another source of marriage penalties for high-income taxpayers because the income at which the exemption phaseout starts for couples is less than twice the starting point for singles. While this is still true under current law, the TCJA increased both the alternative minimum tax exemption and the income at which it phases out, so the alternative tax will affect substantially fewer high-income taxpayers, singles and couples alike.

At the end of 2025, many of the individual income tax provisions of TCJA are scheduled to expire, including those provisions that reduced the prevalence and amount of marriage penalties.

Taxpayers who might qualify for the earned income tax credit (EITC) can suffer particularly large marriage penalties if one spouse’s income disqualifies the couple. However, marriage can increase the EITC (a bonus) if a nonworking parent files jointly with a low-earning worker.

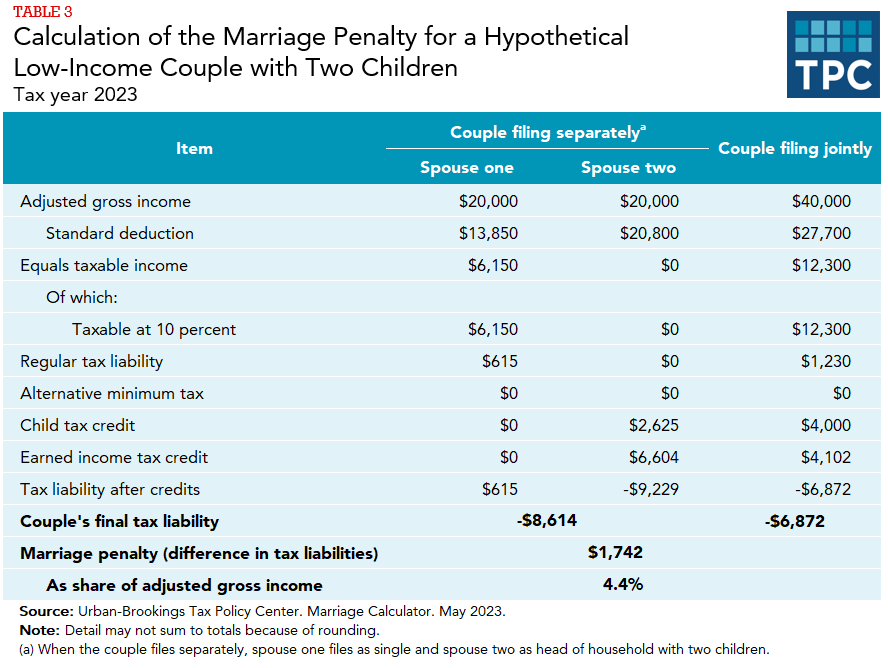

Consider a couple with two children and $40,000 in total earnings, split evenly between spouses (table 3). Two factors would cause them to incur a marriage penalty of $2,070 in 2023.

First, if the couple were not married, one spouse could file as head of household with two children and the other would file as single. Filing in that way, their combined standard deductions would be $34.650, $6,950 more than the $27,700 standard deduction available on a joint return.

Second—and more significant—filing individual returns, the head of household could claim an EITC of $6,933 and a $2,625 child tax credit; the other spouse would get neither tax credit. The head of household would receive a payment of $9,558 and the other spouse would pay $615, yielding a combined net tax refund of $8,943. Filing jointly, the couple would get a smaller EITC of $4,102, somewhat offset by a larger child tax credit of $4,000. Thus, filing jointly, the couple would receive a payment of $6,872, or $2,070 less than they would have if they could have filed separately; the difference equals 5.2 percent of their adjusted gross income in 2023.

Marriage penalties are not confined to the tax system. Married couples often receive lower benefits from government programs than they would if they had not married. Those spending programs—like the EITC—often phase out as income rises. Moreover, the interaction of a tax penalty and a program-eligibility penalty can create effective marginal tax rates that approach 100 percent.

Relative to White couples, Black married couples are more likely to experience marriage penalties and less likely to receive bonuses. TPC estimates that in 2018, 46 percent of Black married couples faced marriage penalties compared to 43 percent of White couples. The gap was even wider for married couples receiving marriage bonuses: 36 percent of Black couples compared to 43 percent of White couples. Among couples paying higher income taxes than if they could file their own individual returns, marriage penalties, on average, represented 1.8 percent of Black couples’ adjusted gross income; the corresponding ratio for White couples was 1.4 percent. Bonuses averaged about 2.6-2.7 percent of adjusted gross income, regardless of race, for couples whose taxes were lower if the spouses filed jointly rather than individually.

Those patterns arise because, controlling for income, Black spouses have more equal earnings than White spouses and because Black couples are more likely to have dependents.

Holtzblatt, Janet, and Swati Joshi, Nora Cahill, and William G. Gale. 2023. “Racial Disparities in the Income Tax Treatment of Marriage.” Washington, DC: Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Further ReadingAlm, James, Sebastian Leguizamon, and Susanne Leguizamon. Forthcoming. “Race, Ethnicity, and Taxation of the Family: The Many Shades of the Marriage Tax/Subsidy.” National Tax Journal.

Bull, Nicholas, Janet Holtzblatt, James Nunns, and Robert Rebelein. 1999. “Defining and Measuring Marriage Penalties and Bonuses.” Washington, DC: The Department of Treasury Office of Tax Analysis Working Paper 82-Revised.

Carasso, Adam, and C. Eugene Steuerle. 2002. “Saying ‘I Do’ after the 2001 Tax Cuts.” Tax Policy Issues and Options Brief 4. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Carasso, Adam, and C. Eugene Steuerle. 2005b. “The True Tax Rates Confronting Families with Children.” Tax Notes, October 10.

Congressional Budget Office. 1997. “For Better or For Worse: Marriage and the Federal Income Tax.” Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Kiefer, Donald and Robert Carroll, Janet Holtzblatt, Allen Lerman, Janet McCubbin, David Richardson, and Jerry Tempalski. 2002. National Tax Journal 55:1: 89 – 1117.

Lin, Emily and Patricia Tong. 2014. “Effects of Marriage Penalty Relief Tax Policy on Marriage Taxes and Marginal Tax Rates of Cohabiting Couples.” National Tax Association Proceedings from the 107 th Annual Conference. Washington DC: National Tax Association.

Steuerle, C. Eugene. 2006. “The Widespread Prevalence of Marriage Penalties.” Testimony before the US Senate Subcommittee on the District of Columbia, Committee on Appropriations, Washington, DC, May 3.

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “Major Enacted Tax Legislation, 2000–2009.” Accessed October 27, 2015.